Clinical

Form and function: Advancing our knowledge of GI health

In Clinical

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Our understanding of many aspects of gastrointestinal function is still in its infancy. There is much to learn about the digestive tract’s importance to people’s health and wellbeing...

Learning objectives

After reading this feature you should be able to:

• Summarise recent research into GI conditions

• Recognise the alarm symptoms that warrant referral

• Explain which medicines might influence gut function

It is a fair bet that one of the next few customers you see as a pharmacist will complain of gastrointestinal symptoms, which range from the irritating but largely benign (e.g. dyspepsia after a heavy meal or mild diarrhoea) to the debilitating and serious, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or coeliac disease.

Gastrointestinal symptoms are a notoriously unreliable indicator of the underlying disease – a dhansak can cause dyspepsia, for instance, but so can upper gastrointestinal and pancreatic cancer.1

Indigestion and heartburn

Dyspepsia refers to symptoms such as epigastric pain or burning, early satiety and a bothersome feeling of fullness after eating.1 The regurgitation of stomach acid in people with gastrooesophageal reflux disorder (GORD), for example, commonly triggers dyspepsia – a quarter of people in western countries experience GORD symptoms at least once a week.2

In more than 70 per cent of people with dyspepsia, endoscopy does not reveal an underlying cause – in other words, they have ‘functional dyspepsia’.3 Essentially, functional gastrointestinal diseases are:

• Chronic: the person has experienced symptoms for at least six months at presentation

• Current: the person has experienced symptoms within the past three months

• Commonplace: the person experiences symptoms, on average, at least one day a week.4 The Rome IV diagnostic system divides functional dyspepsia into:1

• Post-prandial distress syndrome: bothersome fullness after eating or early satiety

• Epigastric pain syndrome: bothersome epigastric pain or burning

• Overlapping syndrome: elements of both syndromes. A recent study of 1,944 adults in the UK found that 5 per cent had post-prandial distress syndrome, one per cent epigastric pain syndrome, and two per cent the overlapping syndrome. So, about eight per cent of adults have functional dyspepsia.3

GORD is usually unpleasant rather than serious. Nevertheless, GORD can cause reflux oesophagitis, oesophageal stricture, Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Between five and 15 per cent of people with chronic GORD have Barrett’s oesophagus, for instance. Of these, up to about 0.5 per cent develop oesophageal adenocarcinoma each year. GORD also contributes to dental erosion, chronic cough, laryngitis and asthma.5

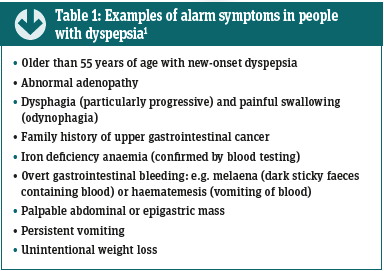

On the other hand, chronic Helicobacter pylori infection, peptic ulcers, upper gastrointestinal malignancies and biliary, gallstone or pancreatic diseases (including cancer) can also cause dyspepsia1, so pharmacists should refer patients with alarm symptoms (see Table 1).

Pharmacists can help reduce the likelihood that a patient develops GORD by offering advice on tackling risk factors. Obesity, for example, alters the pressure across the junction between the stomach and the oesophagus, which makes reflux more likely. Obesity also increases the likelihood of developing a hiatus hernia, which increases reflux frequency and the severity of oesophagitis.

Some people find that a high-fat diet, coffee, chocolate, citrus and tomato products, spicy meals and fizzy drinks can worsen GORD. Numerous studies link smoking with GORD.5 Keeping a diary helps patients identify their triggers.

Pharmacists can suggest several other lifestyle changes that might help to alleviate GORD, such as:

• Not eating before exercise

• Consuming smaller meals

• Drinking between and not during meals

• Not laying down, bending, stooping, or going to bed within two to three hours of a meal.

Elevating the head of the bed and lying on the left side may help if GORD tends to emerge at night.5

Several OTC options can also be suggested, from simple antacids, to alginates, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2 receptor antagonists to alleviate dyspepsia. Alginates, for example, form a ‘raft’ that keeps gastric acid in the proximal stomach.

In a meta-analysis of 14 studies that involved 2,095 people, alginate-based treatments increased the likelihood of resolving GORD symptoms more than four-fold compared with placebo or antacids. Alginates seem to be less effective than PPIs or H2 antagonists (OR 0.58), but this was not statistically significant. The authors suggested considering alginates as an initial treatment for mild GORD symptoms when “chronic acid suppression was either undesirable or deemed unnecessary”.2

Key facts

• About 8 per cent of adults have functional dyspepsia

• A quarter of people in western countries experience GORD symptoms at least once a week

• About 1 per cent of the UK population suffers from coeliac disease

Inflammatory bowel disease

Over the last century, the incidence of IBD – Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis – rose dramatically in the western world before reaching a plateau and, in some places, beginning to decline. Based on 10 studies, the incidence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the UK is 2.4-10.6 and 2-15.6 per 100,000 person years respectively. Worldwide, IBD is becoming more common as newly industrialised countries are increasingly ‘westernised’.6

IBD causes distressing gastrointestinal symptoms including abdominal pain, diarrhoea, rectal bleeding, nausea and vomiting. People with IBD experience periodic exacerbations interspersed by remissions and may develop fatigue, weight loss and fever7, as well as being prone to developing certain cancers. For example, people with ulcerative colitis are 20- to 30-fold more likely to develop colorectal cancer than the general population.8 However, IBD’s carcinogenic potential might extend beyond the gut.

A 10-year study comparing 1,033 men with IBD and 9,306 matched controls found that 4.4 and 0.65 per cent respectively developed prostate cancer – a five-fold difference (hazard ratio [HR] 4.84). The rate of ‘clinically significant’ prostate cancer was four-fold higher (2.4 and 0.42 per cent respectively; HR 4.04). Further studies need to unravel the causes, such as the extent to which chronic inflammation, immunomodulatory treatments, shared genetic risks and other factors contributed.9

Accurate, prompt diagnosis is important to ensure people get effective treatment – which now includes biosimilars – rapidly. However, various conditions can mimic IBD, such as intestinal tuberculosis in people living in or travelling from endemic areas and immunosuppressed patients. Moreover, several drugs – including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), mycophenolate mofetil and an important new group of anticancer drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors – can cause enteritis or colitis that mimic IBD.7 Pharmacists should suggest that people with suspicious symptoms see their GP.

Coeliac disease

About one per cent of the population suffers from coeliac disease, which is triggered by an autoimmune reaction to gluten in genetically predisposed people. People with coeliac disease also develop intense reactions to some, but not all, non-gluten proteins in wheat.10 These reactions cause a range of ‘classic’ symptoms, such as chronic diarrhoea, weight loss and failure to thrive. More common ‘non-classic’ symptoms exclude malabsorption but include iron deficiency, bloating, constipation, chronic fatigue, headache, abdominal pain and osteoporosis.10

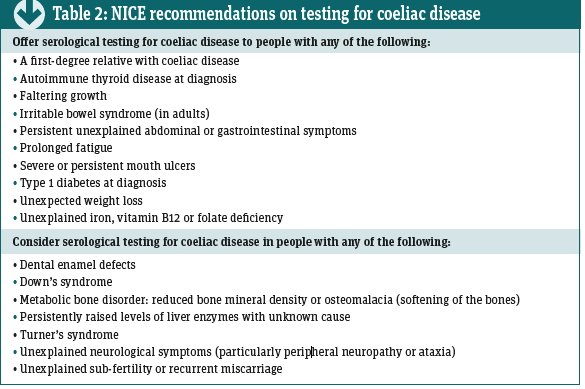

There is a pressing need to improve the speed of diagnosis for this common disease. On average, UK patients report a delay of 13 years between the onset of symptoms and being diagnosed with coeliac disease10 and only about a quarter of people with the condition have been diagnosed.11 NICE has therefore suggested several indications that should prompt testing for coeliac disease (see Table 2) by measuring levels of certain antibodies and, when needed, a duodenal biopsy.10

Usually, avoiding dietary gluten alleviates the symptoms of coeliac disease but adherence can be difficult and some people experience persistent symptoms despite sticking to a glutenfree diet. Several drugs in development target the autoimmune reaction that underlies coeliac disease and, hopefully, will reach prescribers in the next few years.

In the meantime, pharmacy teams can help determine if chronic or recurring diarrhoea might indicate undiagnosed coeliac disease.11 In one study, 15 community pharmacies offered a free point-of-care test to patients whose use of OTC and prescription medicines suggested they may have undiagnosed coeliac disease.

Of the 551 people tested during the six-month study, 9.4 per cent tested positive. Receiving OTC or prescription drugs for IBS, diarrhoea or anaemia were the commonest reasons for offering the test (50.3, 25.8 and 13.4 per cent respectively).11

Irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is another common gastrointestinal complaint, suffered by between 7 and 21 per cent of the population.12 IBS is especially common among women and people younger than 50 years.4 IBS patients experience bouts of abdominal pain and discomfort related to defecation with altered bowel habits, with or without bloating.4,12,13 Patients may report that their IBS is predominately characterised by diarrhoea, mainly constipation or both.12 Pharmacists could use the Bristol Stool Scale to aid their discussions with patients.

IBS begins in the brain or the bowel. IBS, for instance, can arise when a susceptible person – either because of their genes or environment – experiences CNS changes (e.g. anxiety, depression or stress). A pathway linking the brain with the gut increases intestinal permeability causing inflammation and swelling, and altering neuromuscular function.13

In up to half of patients, IBS begins in the bowel. Infection, inflammation, allergic reactions or drugs seem to change intestinal permeability, which alters the gut microbiome promoting inflammation. Changes to the microbiome and inflammation may, in turn, trigger anxiety, depression and other psychiatric symptoms.13

Up to nine out of 10 patients report that certain foods trigger their IBS12 – so the British Dietetic Association recommends advising IBS patients to adopt a healthy diet and lifestyle. Pharmacists can also check whether the person has symptoms suggesting food intolerance (especially to milk and lactose) and advise patients to consider the effect of fibre intake, drinking more fluids, and reducing fatty foods, caffeine, spicy foods and alcohol on their symptoms.12

Again, keeping a diary might help. If these ‘first-line’ changes don’t produce adequate relief, patients may need further advice from a dietician.12

Medicines and the bowel

Numerous widely used drugs can influence the bowel. Low-dose aspirin, for instance, increases the risk of gastrointestinal ulcers and serious bleeds between two- and four-fold. The risk rises further in people also taking other antiplatelet medications, NSAIDs, alcohol, those who are infected with H. pylori and those who are older.

The gastric mucosa of older people shows, compared to their younger counterparts, impaired defences – increasing the likelihood of injury from aspirin, alcohol and other chemicals – and reduced abilities to heal.14

Against this background, aspirin increases the risk of gastrointestinal ulcers and bleeding through three mutually reinforcing actions. Firstly, low-dose aspirin is antithrombotic, which reduces haemostasis. Secondly, by inhibiting production of prostaglandins E2 and I2 (prostacyclin), aspirin impairs mucosal integrity and defences. Thirdly, aspirin seems to reduce the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis), which further impairs mucosal healing.14

Aspirin isn’t the only drug to influence the gastrointestinal tract. Several drugs – including NSAIDs, some antibiotics (e.g. tetracyclines), statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, oral and inhaled corticosteroids, and calcium channel blockers – can cause GORD symptoms.5 Moreover, about 40 and 90 per cent of people taking opioids for non-cancer and cancerrelated pain respectively develop constipation.4

In addition, several drugs affect gastrointestinal transit time – but before blaming a drug, pharmacists should rule out potential lifestyle factors. In a recent study, of the people who were not taking drugs that might influence gut motility, women were almost four times (OR 3.9) more likely than men to show a transit time longer than the median of 2.35 days.

Smokers were almost twice as likely as non-smokers to show prolonged transit times. Nevertheless, in men and women, prolonged transit times were less common in those not taking a drug that affects motility than in those who were.

The gastrointestinal tract is more than a simple nine-metrelong tube connecting the mouth with the anus. We’ve not had space to focus on, for example, the enteric nervous system, which contains some 100 million neurons – about the same as the spinal cord. Nor have we considered the microbiome – some 30,000 strains of bacteria colonise the lower GI tract, which contribute to drug metabolism and numerous physical, psychological and neurological diseases. Nor gastrointestinal hormones, which contribute to, for example, type 2 diabetes. We shall be returning to look at these areas in a future article.

Over the last century, the incidence of IBD – Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis – rose dramatically in the western world before reaching a plateau and, in some places, beginning to decline. Based on 10 studies, the incidence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the UK is 2.4-10.6 and 2-15.6 per 100,000 person years respectively. Worldwide, IBD is becoming more common as newly industrialised countries are increasingly ‘westernised’.6

Over the last century, the incidence of IBD – Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis – rose dramatically in the western world before reaching a plateau and, in some places, beginning to decline. Based on 10 studies, the incidence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the UK is 2.4-10.6 and 2-15.6 per 100,000 person years respectively. Worldwide, IBD is becoming more common as newly industrialised countries are increasingly ‘westernised’.6